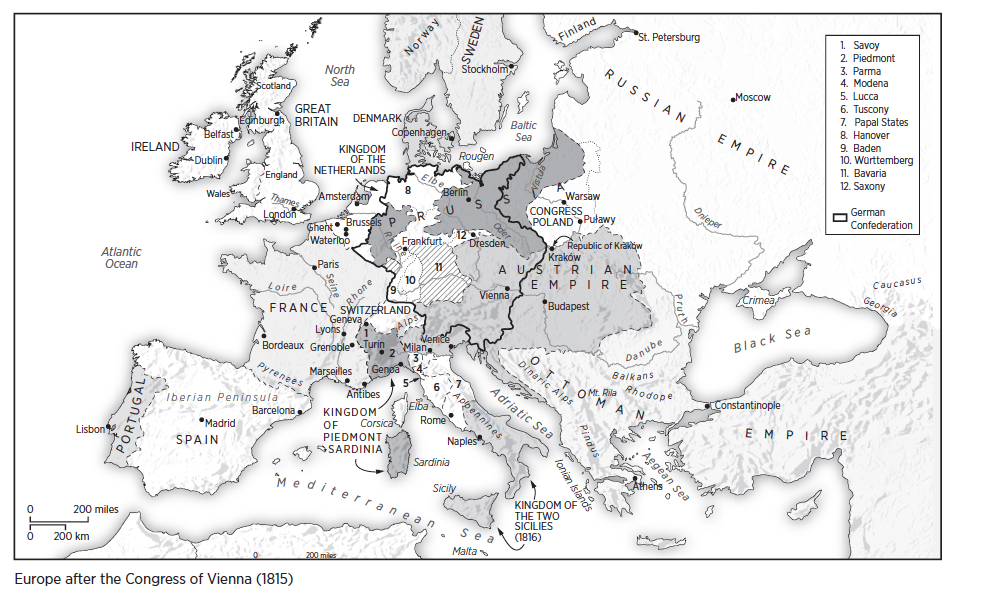

In early September 1814, carriages from throughout Europe were rolling across hot and dusty roads on their way to Vienna. In response to a public invitation from the victorious allied powers, monarchs, ministers, and dignitaries of every conceivable status and description were descending upon the Habsburg capital to participate in the reconstruction of Europe. The visitors included the Emperor of Russia, the Kings of Prussia, Bavaria and Denmark, scores of princes and high ranking nobles, German imperial knights, ambassadors, scholars, musicians, artists, writers, cooks, tradesmen and servants in the thousands. Most of them, as it turned out, would play no role at all in the high-stakes diplomacy to be conducted behind closed doors, but their presence provided a splendid backdrop and a fitting end to two decades of revolution and war. The Congress of Vienna and the so-called ‘Congress System’ that dominated Europe for the next ten years can best be understood as reactions to the previous epoch. The very fabric of European political and social life had been torn asunder by the French revolutionaries and decades of warfare with Napoleon. The challenge of the postwar period was to come to terms with these new forces while restoring the rudiments of order and stability lost in the years of revolution and strife. Although the French Bourbons and other toppled dynasties were suddenly restored to their thrones, the statesmen at Vienna recognized there could be no turning back of the clock to the days of the ancien régime, whose very imperfections had led to revolutionary upheavals. The Congress statesmen looked in part to a reshaping of the international system to provide an anchor for maintaining the existing social order.

--from the Preface to The Congress of Vienna and its Legacy.