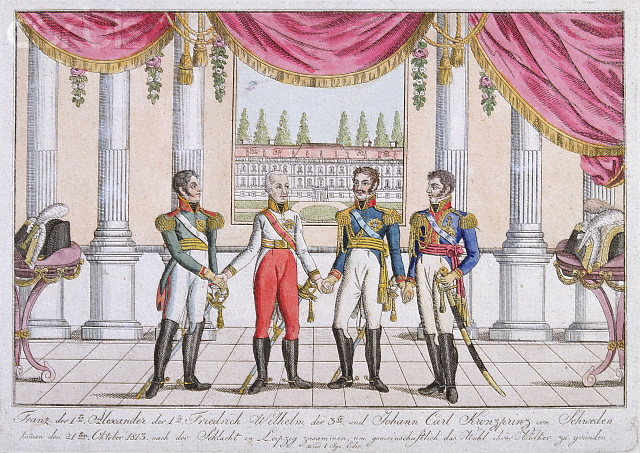

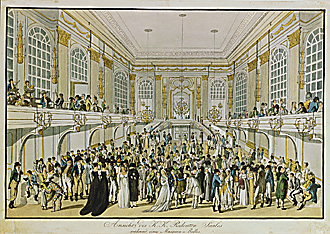

The statesmen who gathered in Vienna had already experienced twenty-five years of revolution and war. What had they learned from the experience? Above all else, they had learned the necessity of frequent communication, a willingness to consider views from other vantage points, the benefits of cooperation and a respect for limits. These qualities, which had held the alliance together in the final campaign against Napoleon, were now carried over into peacetime. In the autumn of 1814, as the culmination of their struggles, they gathered in Vienna.

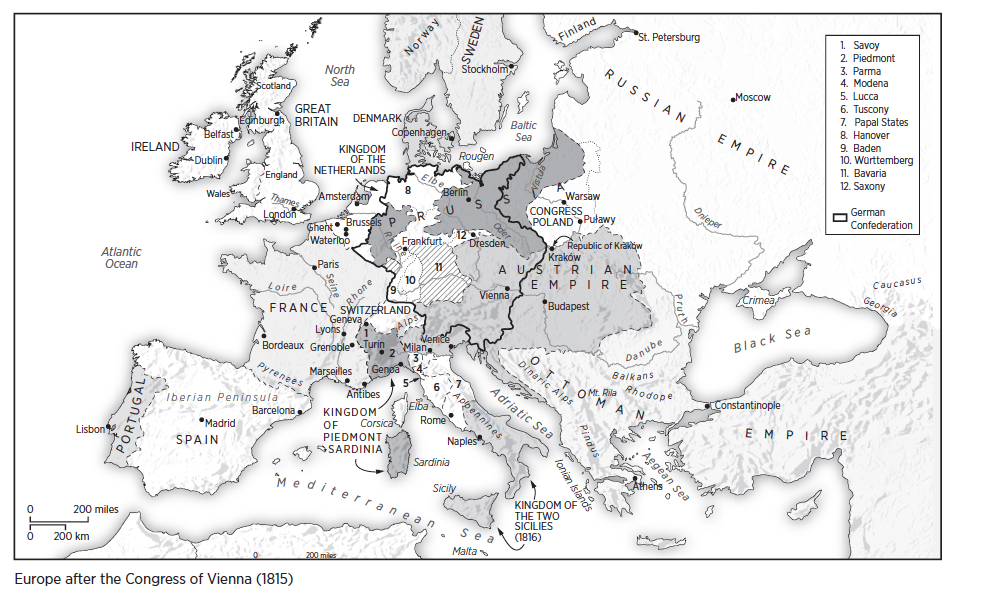

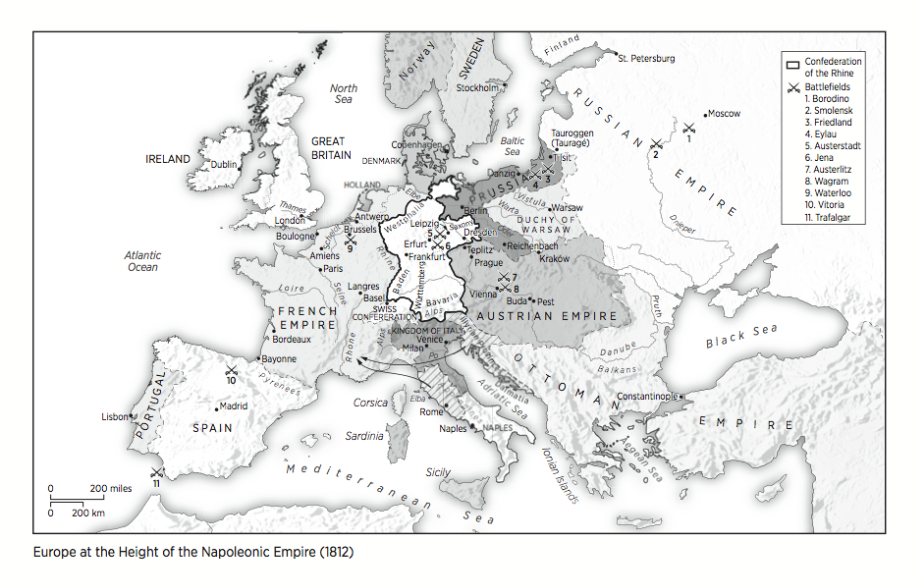

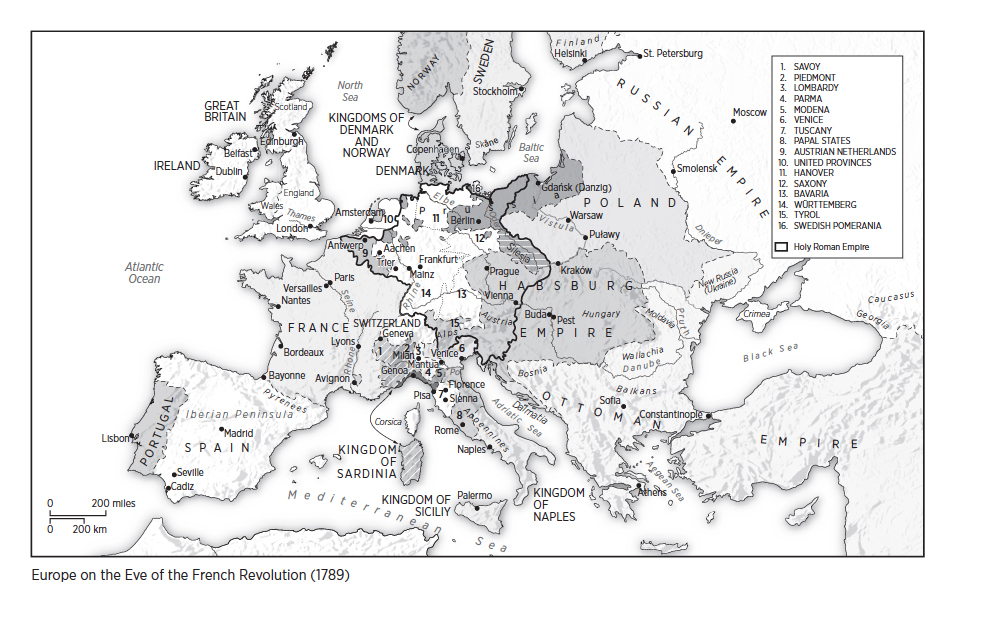

Were they far-seeing architects, as some now claim? Or frightened reactionaries? Did they create a new world order or simply restore the old? The answer lies somewhere in between. The French Revolution had constituted a profound break with the past. The men of 1814, having vanquished Napoleon and dissolved his empire, had now to determine the future of Europe. They faced an opportunity unprecedented in modern history. Under Napoleon’s ruthless hand, new states had been formed and destroyed with dazzling complexity and at dizzying speed. But now the game of musical chairs was about to cease. Where were the new frontiers of Europe to be drawn?

In considering their work one might start, as the allies themselves did, with France. The men of 1814 are often complimented for their foresight in inviting France to the negotiations. In truth, the arrangements with France had already been determined in the Peace of Paris the previous May. That peace was, however, a negotiated settlement, not a coerced Diktat in the sense of the later Treaty of Versailles in 1919. The reason for this leniency had less to do with Talleyrand’s skill in diplomacy than with the views of the allied statesmen on the nature of the enemy. That enemy was the French Revolution. After 25 years of war and turmoil, they saw Napoleon primarily as the military face of that primordial force. The Bourbon king of France, Louis XVIII, was their ally. They therefore did not want to impose a punitive treaty that would undermine his authority and make the Bourbons unpopular throughout their own kingdom. If only the peacemakers of 1919 had also exhibited such foresight!

Then we could turn to the Netherlands. As Professor Nicholas Van Sat has recently shown, from the very first, the future of the Netherlands was prominent in the thinking of the allies. It was fear of French control of the Scheldt that had brought the British into the war in 1793. As early as 1795, the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Grenville, had proposed that the Netherlands be strengthened by the addition of Belgium; the Ábbe de Pradt had proposed the same solution in 1800. Prince Adam Czartoryski—then Russian foreign minister—proposed that the Netherlands be awarded its independence in his initial overture to Pitt in 1804. In his response of January 1805, Pitt attempted to create territorial barriers against French aggression, chief of which was a stronger Netherlands. Pitt proposed that Belgium be divided between Holland and Prussia. Under Napoleon, the Netherlands was then reduced to the puppet Kingdom of Holland under the rule of his brother Louis in 1806; in 1810, Napoleon then directly annexed the Netherlands to France. Prince William of Orange finally returned after the withdrawal of French troops in November 1813. Meanwhile, Castlereagh carried Pitt’s master plan with him when he travelled to the Continent in December 1813; and he laid this plan before the House of Commons when he later returned in triumph from the Congress of Vienna. In the first Peace of Paris, the allied powers and France agreed that Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands should be united under one rule. The decision to establish a monarchy, however, was taken solely on the initiative of William of Orange. Castlereagh refused to dictate the internal arrangements of the Netherlands, though he was, of course, overjoyed with the results. At the same time, the British refused to return all of the former Dutch colonies and kept some of the most important, such as Capetown, for themselves.

Meanwhile, the reconstruction of Central Europe was far more problematic. In fact, this posed the main problem at the Congress of Vienna since the question of the new borders fo France were already out of the way. The Tsar proposed to right the wrongs of his grandmother Catherine the Great by restoring Poland, which had been effaced from the map of Europe. However, to placate the Russian nobility he also had to guarantee that the new Poland would not be a threat to Russia, a trick he neatly pulled off by creating a Kingdom of Poland with its own institutions but with himself the Tsar as King. Thus he would restore Polish territorial integrity and even Polish institutions but not its independence. Metternich and Castlereagh were sceptical and saw his plan merely as a new form of Russian aggrandizement. But the close cooperation of the allied leaders in the last months of the campaign against Napoleon dictated the course that their dispute took and in the end, despite some sabre-rattling, avoided a renewal of the war. In an elaborate minuet, Prussia began in league with Russia, then moved over to the two allies, Austria and Britain, and finally gravitated back to Russia. These oscillations can be explained in part by Prussian interests but more so by bureaucratic politics and the different perspectives of Hardenberg and his sovereign. In December 1814, some observers even thought the former allies might even go to war over this issue. Prussian and Austrian generals prepared their troops, and Grand Duke Constantine of Russia told Polish troops that they should get ready to defend themselves. Britain and Austria even signed a mysterious secret treaty of alliance with their former enemy, France. But in the end, cooler heads prevailed. After a month of negotiations in January 1815, the powers finally settled on a compromise, reached by adding and subtracting populations based on the results of a specially appointed Statistical Committee.

In the end, the Tsar succeeded in taking most of Poland; Kraków became independent; and Prussia was given a large section of Saxony but not the whole kingdom. The Netherlands and Hanover contributed to the solution by making even further territorial cessions to Prussia after the Hundred Days. Castlereagh and Metternich nonetheless proved right in thinking that Poles could not maintain their autonomy in such a setting. After an attempted revolution in 1830, Poles under Russian rule lost most of their privileges.

While Poland remained divided, Germany was simplified and the 39 German states were united for the first time in a loose confederation.

In Italy, too, the men of 1814 faced the task of reconstruction. Here again, Napoleon had replaced traditional boundaries with a bewildering succession of new states. The statesmen at Vienna could not put back the clock, but they placed Habsburg princes on several of the Central Italian principalities, while they strengthened the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia as another barrier state cradling France. One key issue they faced at Vienna was whether to topple Napoleon’s brother-in-law, Joachim Murat, as King of Naples—a problem that Murat solved himself when he allied with Napoleon during the Hundred Days.

The decisions at Vienna were not confined to territorial arrangements alone. The statesmen at Vienna guaranteed the neutrality of Switzerland, discussed protections for German Jews and the abolition of the slave trade, established new rules for diplomatic precedence, and created the Central Commission for the Navigation of the Rhine.

At Vienna, the allied leaders also discussed the possibility of signing a general guarantee--an agreement by all states to respect one another's borders and governments--and thus end the practice of war. This project could trace its roots back to have the dreams of the philosophers of perpetual peace—the Duc de Sully, the Abbé St Pierre, Rousseau, and Kant—each of whom had envisaged a confederation guaranteeing its member states against all changes by force. In 1805, Prince Adam Czartoryski had proposed just such a system to the Tsar, who was much taken by it. The British Prime Minister William Pitt, Castlereagh's mentor, also saw some value to it. In 1815, Castlereagh raised the issue at the Congress of Vienna, bringing the Tsar to tears of joy. The proposal would have guaranteed all rulers and their thrones. However, the proposal foundered because of the uncertainty surrounding the Ottoman Empire. The signatories did at least issue the Vienna Final Act, which made every state a party to the territorial settlement. Establishing a system of perpetual peace was also one of the chief aims of the Tsar’s ecumenical Holy Alliance, a league of Christian brotherhood proclaimed in September 1815 and signed by most European rulers.

For their territorial arrangements alone, these men would have been remembered, but in fact they did much more. While still at Vienna, they suddenly faced the greatest challenge of their careers. In March 1815, Napoleon escaped from his place of exile in Elba and landed in the South of France. From there, he marched triumphantly to Paris. Not a single shot was fired in favor of the restored King, Louis XVIII. When news first reached Amsterdam, William offered Louis the use of Dutch troops, which the latter ignominiously refused. A week later, Louis was in flight, and sought the protection of the King of the United Netherlands in Ghent, where he stayed for les Cents Jours—the Hundred Days. The allies, despite their prior disagreements, stood remarkably firm. Napoleon hoped to defeat the British and Prussians on the field before the arrival of the Austrians and Russians, but his plans dramatically failed on the hilly and blood-soaked field of Waterloo.