What Can You Learn by Reading This Captivating Book . . .?

PART ONE: WAR

CHAPTER 1. THE EUROPEAN STATE SYSTEM AND THE NAPOLEONIC WARS

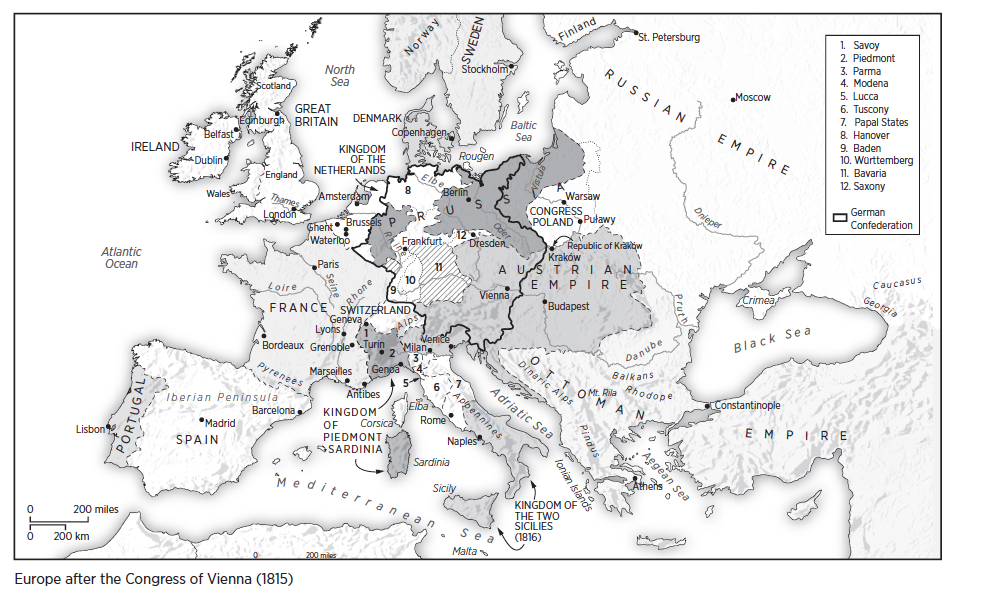

It is impossible to understand either the Congress of Vienna or the Congress System without some appreciation of the conditions of the ancien regime. This first chapter sets the stage by describing Europe on the eve of the French Revolution, including its diverse range of sovereign entities from tiny city-states to gargantuan multinational empires, and the specific geopolitical ambitions of the leading powers. The French Revolution challenged this existing order and plunged Europe into twenty years of war. France first progressed from a monarchy into a revolutionary republic, and then further transformed itself into an imperial, hegemonic power under Napoleon’s scepter. An important exchange of ideas in 1804-1805 between Polish Prince Adam Czartoryski and British Prime Minister William Pitt for the postwar reconstruction of Europe foreshadowed many of the ideas of the Vienna Congress. The chapter ends with a description of the Napoleonic Empire at its height, on the eve of the French invasion of Russia.

CHAPTER 2. THE COLLAPSE OF THE NAPOLEONIC EMPIRE

In this chapter, you will see how the allies finally organized an effective coalition capable of defeating Napoleon. You will learn about British Foreign Secretary Lord Castlereagh’s mission to the Continent in December 1813, the reasons for the failure of the negotiations between Napoleon and the allies at Chatillon in early 1814, and the terms of the Treaty of Chaumont, in which the allies pledged not only to remain united until the defeat of Napoleon, but also to continue their wartime alliance into peacetime—a decisive step in the genesis of the later “Congress System.” You will also examine the factors behind the return of Louis XVIII to the French throne (the Bourbon Restoration), as well as the terms of the First Peace of Paris (May 1814), concluded between Bourbon France and the allied powers, which issued an invitation to other states to attend the Congress of Veinna. The allied leaders actually intended to settle their own differences before the Congress met—so that the Congress would merely rubber-stamp their own decisions—but their plans were stymied by their continuing disagreement over the reconstruction of Central Europe, especially Poland and Saxony.

PART TWO: PEACE

CHAPTER 3. THE CONGRESS OF VIENNA, 1814-1815

In this chapter, you will learn about the territorial aspirations of each of the “great powers” on the eve of the Congress, and compare the backgrounds and personalities of the four leading participants—Tsar Alexander, Prince Metternich, Lord Castlereagh, Prince Hardenberg and Prince Talleyrand. The chapter also considers several approaches that might have been adopted for the reconstruction of Europe, including the doctrines of dynastic legitimacy, nationalism and the balance of power.

From here, you will turn to the main developments in the diplomacy of the Congress itself. From September to October 1814, the so-called “Procedural Question” loomed large. The victorious allied powers faced the problem of what to do with all of the delegates who had assembled in Vienna, while they worked out their own differences in private conferences. Talleyrand, the wily French minister who had survived a dazzling succession of regimes, boldly claimed that he was able to upset the alliance and bring France back into the circles of the great powers by championing the rights of the lesser states, but there is little truth to his claim. Meanwhile, the four victorious allied powers were engaged in a deadly dispute over the “Polish Question”—Tsar Alexander’s plan to reconstitute Poland (which had been completed effaced from the map by the partitions of 1772, 1793 and 1795) as an independent kingdom within the Russian empire, with himself as Polish king. Castlereagh and Metternich attempted to resist the Tsar’s plan by first cooperating with Prince Hardenberg of Prussia, but this strategy failed when the King of Prussia and the Tsar retreated to Budapest in late October 1814 and the king repudiated Hardenberg, his own chief minister. Eventually, Russia took most of Poland; and Prussia was strengthened with part of Saxony and non-contiguous territories in the west.

In this chapter, you will also learn about the fascinating social life of the Congress, allied plans to overthrow Napoleon’s brother-in-law Murat, the creation of the German Confederation, allied consideration of the rights of German Jews and the abolition of the slave trade, the drafting of the Vienna Final Act, and the question of whether the powers should agree to a “General Guarantee” of the settlement as part of a new world order. The chapter ends with an analysis of later assessments of the territorial settlement by both historians and political scientists.

CHAPTER 4. THE BIRTH OF THE CONGRESS SYSTEM, 1815-1818

Several recent books on this subject end with the Congress

of Vienna, but in fact this is really only part of a larger

story. In March 1815, the deliberations of the Congress

were suddenly interrupted by the startling news that

Napoleon had made a daring escape from Elba and landed

in the South of France. Over the next few days, the

delegates learned to their chagrin that the Bourbon regime

in France had collapsed without a single shot being fired

in its defense. During the “Hundred Days” (les Cent-Jours)

from March to June 1815, Napoleon returned to the

throne of France.

In this chapter, you will learn about the “Congress

System”—a formal system of periodic reunions by the heads of state and chief ministers of the great powers—which was

instituted in direct response to this crisis. The collapse of the Bourbon monarchy demonstrated to allied leaders that far stronger measures were needed to stifle the flames of revolutionary enthusiasm than they had adopted in 1814. In fact, the allied

leaders initially disagreed on just how to respond to the ignominious flight of Louis XVIII. The British remained the most favorably disposed towards the Bourbons while the Tsar opposed the return of the Bourbons altogether and favored placing the Duc d’Orléans on the throne. But, as this chapter shows, it was Wellington who took control of the situation. In the aftermath of Waterloo, he virtually dictated the return of Louis XVIII to the French as the price of peace. Afterthe French King's second restoration, the allies put in place a series of rigorous measures to ensure future French stability—including further French territorial concessions, the payment of reparations, pressure on the French to punish some of the leading traitors, the extended occupation of France by allied troops, and the creation of an ambassadorial conference in Paris to advise the king. The keystone of this new system was the creation of the Quadruple Alliance—a solemn treaty engagement by the four allied powers to hold periodic reunions at fixed intervals and to consult one another in the event that revolutionary disturbances ever again erupted in France. The Tsar simultaneously introduced the “Holy Alliance,” originally intended as a

spiritual alliance of Christian peoples, but transformed by Metternich’s editing into a

conservative coalition of monarchs.

An allied occupation force remained in northwestern France for three years until the

early payment of reparations—financed through loans—led the allies to end their

occupation ahead of schedule. The decision to remove these troops from France led

to the Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle (Aachen) in 1818—the first great reunion of

allied leaders after the Congress of Vienna and the negotiation of the Second Peace

of Paris.

With monarchical power apparently secure in France, a new issue emerged at Aix: should

France be welcomed as a full member of the alliance—transforming the Quadruple

Alliance into a European Pentarchy? Europe would then be controlled by a virtual

super-government—an Aeropagus—composed of the five great powers. Castlereagh

argued strenuously for a narrower conception of the alliance, which, he claimed, had

been established solely to protect Europe from French aggression. The Tsar at first appeared to agree, but then proposed that a separate league of all European states (including France) should be created, to co-exist alongside the Quadruple Alliance. The league would then guarantee the safety of all its members. The Tsar coupled this with a proposal for constitutional reform within each state. Europe would thus be transformed into a federation of constitutional states immune from revolution. In this way, Alexander hoped to achieve the dream of the eighteenth-century philosophers for perpetual peace, imbued with the spirit of Christian brotherhood. Castlereagh adamantly opposed this scheme, arguing that it would simply keep all Europe fettered to the status quo, protecting existing rulers without regard to their actions. In the end, Castlereagh’s views prevailed. The Quadruple Alliance was renewed without France, but it was agreed that France should participate in all future allied reunions, henceforth to be held on an ad hoc rather than a periodic basis.

PART THREE: DIPLOMACY

To Learn More About These Fascinating Topics, Buy the Book . . . .

CHAPTER 5. THE ALLIANCE IN OPERATION, 1819-1820

CHAPTER 6. RIFT AND REUNION, 1820-1822

CHAPTER 7. THE TWILIGHT OF THE CONGRESS “Peterloo Massacre” in Manchester, August 16, 1819

SYSTEM, 1822-1823

CHAPTER 8. THE LEGACY OF THE CONGRESS

SYSTEM: SUCCESS OR FAILURE?

The final chapter addresses the transformation of European

relations after the eclipse of the Congress System, as well as

interpretations of the Congress System and the continuing

impact that the Congress of Vienna and the Congress System

still has on us today.